Or checkout the ‘Hollywood Heist’ backlot.

Image: BBC/Bronte Film

From: https://metro.co.uk/2020/08/13/holliday-grainger-strike-robin-getting-together-where-go-13124664/

Hola amigos,

There are three states of information in a book. You either know:

More than the hero

Less than the hero

The same as the hero

And the particular state you are in is what is called the Narrative Drive. This is what keeps you turning pages.

*Many of my lessons in story fundamentals have started with the teachings of Shawn Coyne—storygrid.com—if you're feeling particularly nerdy. You've seen his name here before.*

You'll be thrilled to know I've finally finished up Silkworm, the mystery novel by Robert Galbraith and so I'll tell you which fuel he uses to keep us up past our bedtime. It's #2 - you know less than the hero

**Don't worry, no spoilers**

As we get towards the end of the book t's revealed to the reader that Cormoran Strike (our private-eye hero) has a theory of how the crime happened BUT you aren’t given the details. You're just told that he knows.

Like this:

Example 1 - Cormoran enlisting the help of a friend

The engineer, over a hundred miles away in his sitting room in Bristol, listened without interrupting while the detective explained what it was he wanted done. When finally he had finished, there was a pause.

Example 2 - Prior in the story, when Cormoran first tells his assistant, Robin that he has a theory

Still wearing his coat he sat down on the leather sofa and talked for ten solid minutes, laying his theory before her in detail.

Galbraith isn't shy about the fact that Cormoran knows more than you. She stands on it outright and let's you enjoy every last second. Here's one more.

Example 3 - Robin is given a job to do

Robin, at least, had a meaningful job to do, although she felt that she was letting Strike down. She had returned to the office two days running with nothing to show for her efforts, her evidence bag empty.

(I don't have to tell you that Galbraith doesn't bother to tell us what exactly Robin is up to.)

But the enjoyable curiosity keeps you sticking around to watch him prove out the mystery he's already solved in his head. Reminder - It's the hack writer that merely lines up cheap cliff hangers. A satisfying pace of revelation is what we need.

That's an example that comes from a mystery. So, when do we see the other fuels?

I'm no expert but I think fuel #1 (when you know more than the hero) is more widely used in horror stories. You know, like: 'Don't open that door!'

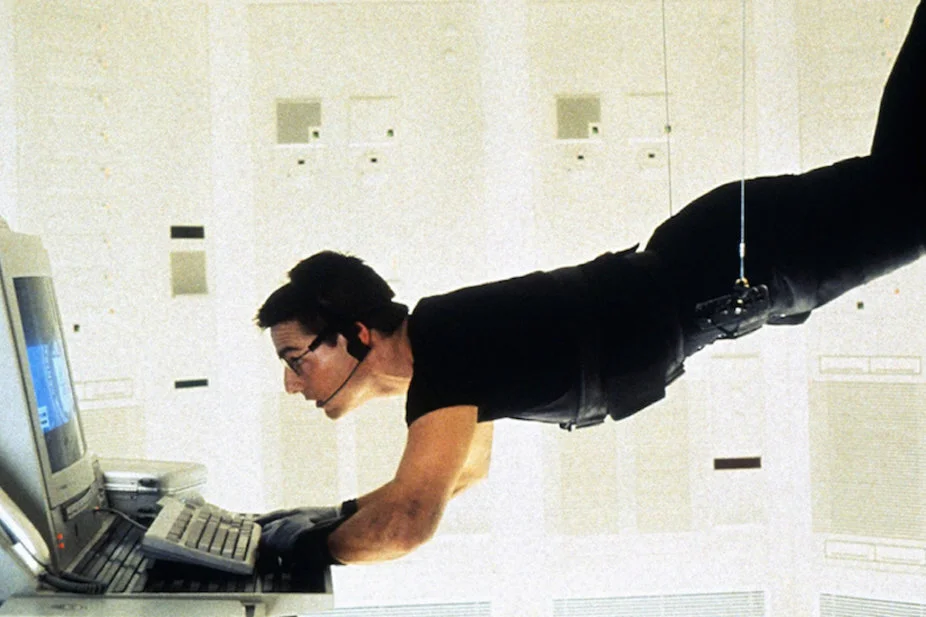

#3 (when you know the same amount as the hero) is used a lot in action. Indiana Jones, Mission Impossible. You're along for the ride.

But of course, there is one twist when we talk about the narrative drive fuel in heists. Think about what do these scenes have in common:

Ocean’s 11:

Bruiser, the goon sent to beat up Danny was actually on Danny's payroll

Image: Warner Bros. Picture

from: https://getyarn.io/yarn-clip/64a6104d-8850-4fb1-9c67-5860449d2788

The Thomas Crown Affair:

Thomas Crown upon giving himself up actually had a secret plan to fool the police all along.

Image: MGM Distribution Company

The narrative drive here is a twist on #2: You know less than the hero but you didn't know you knew less, until it's revealed

Unlike with Cormoran, who will sit you down and tell you in advance that he's solved the mystery, in a heist the hero surprises you with the information she or he had up their sleeve.

I realize this isn't some huge secret that I'm telling you but I do think putting into a little framework like this is quite cool, putting a little science to the art. You know me, being a Virgo and all.

In summary, you can know more, you can know less, or you can know the same as your hero. And in a heist you can know less without knowing you know less.

Happy Friday,

Charlie

Have some thoughts? Feel free to drop a comment or hit me up: charlie@charleskunken.com

Please judge.